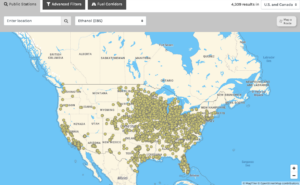

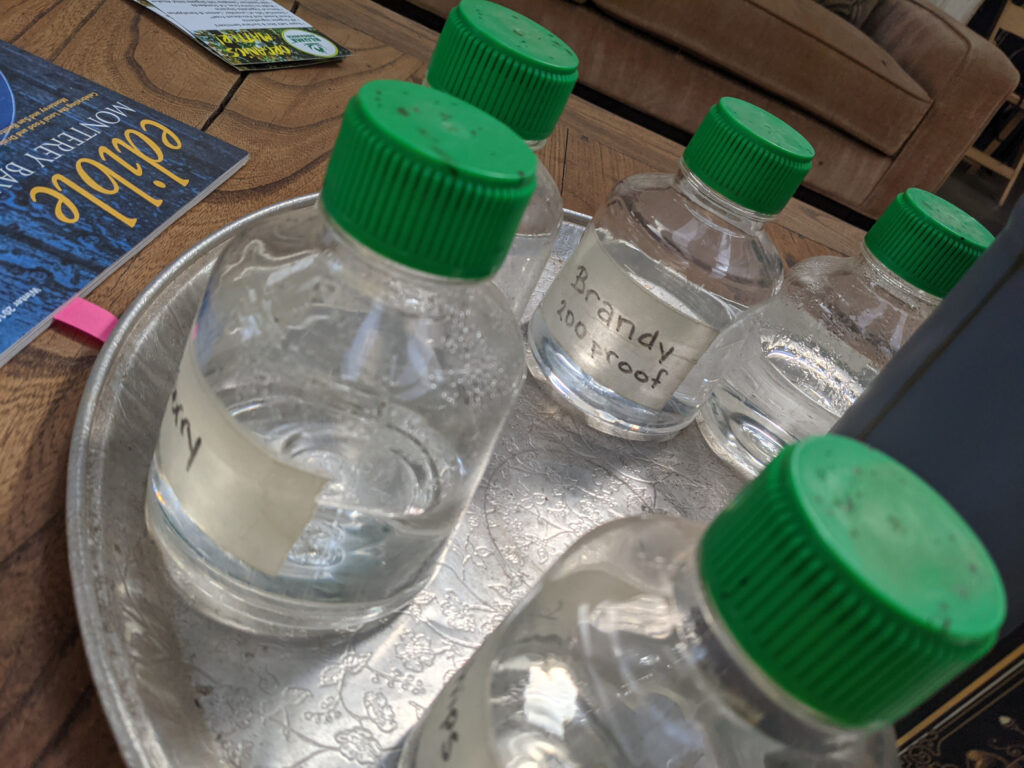

Whiskey Hills and Blume Industries can convert everything from walnut husks to surplus candy into fuel, pharmaceutical-grade ethanol and spirits of varying proofs. PHOTO: Mark C. Anderson

We are pleased to share, with permission, the following article, Whiskey Hill Farms’ Clean-Fuel Revolution, from the Good Times newsletter, September 20, 2022, by Mark C. Anderson:

Whiskey Hill Farms’ Clean-Fuel Revolution

The Watsonville operation’s mastermind David Blume’s big picture also involves preventing food waste and hunger on a global level

Way out off a rural road in Watsonville, a full-on tropical forest bursts with life. Hundreds of fruiting plants, 450 all told, fill a large greenhouse. The jungle pops with passionfruit blossoms, big bunches of bananas, mountain papayas, tropical spinach and multiple types of South American “tree tomatoes” (aka tomarillos).

But it’s just one of the fascinating elements at Whiskey Hill Farms. So many eye-catching things are thriving here, in fact, that it can be easy to miss the big picture—even if the big picture involves preventing war, food waste, hunger and carbon monoxide poisoning.

Some species in the tropical forest are so rare Whiskey Hill owner David Blume and his team share cuttings with conservation groups worldwide.

“If it wasn’t for us protecting them, there would be no way to recover from the devastation of their habitats,” he says. He does add that it’s not a purely altruistic endeavor, as they want to bring a number of the curated fruits to market.

Another wonder is the zero-emission research-and-development distillery that can convert food scraps, crop surpluses, Halloween candy and eventually plastic into alcohol that cleanly and cheaply fuels ovens, cars, boats and buses—or can be made into things like organic sanitizer and vodka. The distillery is technically the work of WHF sister LLC Blume Industries, but they’re so integrated they’re essentially inseparable.

It’s about as far away from burning coal or oil as it gets. As one Whiskey Hill/Blume Industries slogan goes, “Real environmentalists don’t burn dinosaurs.”

Around the corner sits a permaculture nerd’s fever dream, a slick and multi-functional ecosystem that closes the bio refinery’s loop by transforming potential waste streams into more positives.

Carbon dioxide from fermenting in the distillery feeds into another huge greenhouse, boosting the yield of Skittles-colored cherry tomatoes, sweet bell peppers and broad-leafed wasabi.

Hot water from the distilling process and compost-heated water pipes provide radiant heat beneath grow beds.

Additional effluent from making alcohol runs into a methane digester that spits out natural gas that powers the biorefinery’s boiler. The system also sends nutrient-rich water into a marsh, which in turn filters the water for the adjacent catfish pond (aka bonus sustainable protein)—while growing starchy cattails perfect for making more fuel.

The pond’s fish poop can be used as fertilizer for crops. Other plant juice runoff from the still can also be converted into fertilizer.

In short: zero landfill, more synergy, maximum production. It all vibrates with another one of Whiskey Hill’s mottos: “There is no such thing as waste.”

“Everything that comes out of that system gets used,” Blume says. “There’s no leftovers.”

Andy Martin of Pajaro Valley-based A&A Organic Farms has been helping Whiskey Hill find a buyer for its turmeric and tomatoes for 20 years, so he is well-acquainted with the wonderland.

“It’s like the Winchester Mystery House of farms,” he says. “David’s our mad scientist and always has something groovy-crazy going on.”

That’s why it would be understandable if visitors missed the bigger reality. Tom Harvey, executive vice president of Blume Distillation and spokesperson for the farm, helps provide perspective.

“We want to solve fuel scarcity, energy shortages, lack of local jobs and environmental remediation challenges,” he says. “That’s what our work is really about.”

Each of those issues presents pressing challenges. And recent events and rule changes are only adding to the urgency.

PLANTS INTO FUEL

As a kid in the 1960s, Blume helped his dad tend crops on a San Francisco city lot.

“It’s not what I thought about doing for the rest of my life as an occupation, though I knew I wanted to grow vegetables for myself,” he says. “Being a teenager is really hard, and growing my own food taught me I could put energy in and get energy out. I was getting through angst by growing food for my family. Besides, it was quiet in the garden.”

He would go on to study ecological biology and biosystematics at San Francisco State, teach similar disciplines and even do gig work on behalf of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. For NASA, the goal was to determine if it was possible to sustain an island hotel on purely solar energy—processing sewage, distilling water, generating electricity.

As Blume says, “To prove it can be done, as if the hotel was in outer space.”

When the 1970s energy crisis descended, he developed the nonprofit American Homegrown Fuel Co., teaching thousands how to make and produce alcohol fuel on the cheap at home—from waste streams like food scraps—or on the farm, with enough land.

When Bay Area radio station KQED invited him to participate in a series called “Alcohol as Fuel,” he wrote a companion manual called Alcohol Can Be a Gas!, with a foreword from legendary architect and systems theorist R. Buckminster Fuller, who would call Blume to discuss designs.

The original collaboration call came when Blume was 26 years old and dead asleep in the middle of the night.

“The guy on the phone says, ‘I’m Buckminster Fuller, and I want to talk about something I’m designing,’” Blume recalls.

His response: “If you are who you say you are, tell me the net primary productivity of the Earth.” (NPP is the amount of biomass or carbon produced by primary producers per unit area and time, obtained by subtracting plant respiratory costs from gross primary productivity or total photosynthesis.)

The man Blume still calls “Bucky” nailed the figure. Then they talked for four hours, into the wee hours.

“He told me he liked the way I thought,” Blume says. “Then he said, ‘I think we’ve got it,’ and hung up. I wondered, ‘Did I just drop acid?’”

The discussions went on for years. Today, the updated Alcohol Can Be a Gas! fills 640 pages, 8-1/2-by-11 inches each, with 514 charts, photos and illustrations. It dives deep into how alcohol isn’t a new fuel, but one that predated oil as a primary option, buried by Prohibition and oil’s cutthroat-competitive (and effective) messaging. It also reveals how easy it is to use alcohol with existing combustion engines after simple adaptations.

Amphibian habitats called “frog condominiums” by farm staff provide homes for frogs that eliminate pests without chemicals. PHOTO: Mark C. Anderson

Like the thriving stimuli at Whiskey Hill, the information can be a lot to take in, but it boils down to some fundamentals: You can turn plants into fuel—“liquid sunshine,” Blume likes to call it—which means with enough sun you’ll never run out of gas. You may make fuel from carbon dioxide-sequestering plants, reversing greenhouse effects. You need no new technology. You end up with byproducts that are clean and useful. You can do it with abundant food waste.

To simplify further: One person’s trash can be everyone’s treasure.

TIME HAS COME

As another gas crisis surfaced this year with the war in Ukraine, Blume found new motivation to leverage his knowledge to make a case for alcohol.

Another bit of motivation in 2022 goes right back to Blume’s waste-free ways: California Senate Bill 1373 went into effect in January, mandating counties to do something with their organic scraps other than chucking them in the landfill. Suddenly, cities from Arcata to Artesia are sussing out ways to deal with waste wisely.

Meanwhile, as part of a bold plan to fight climate change, state regulators approved a policy last month stopping the manufacture, sales and use of gas-powered vehicles by 2035 in California, the largest car market in the country, with interim reduction goals along the way.

This month, lawmakers followed that with a record $54 billion in climate spending and passed extensive new limits on oil and gas drilling. That came paired with a mandate that California stop contributing carbon dioxide to the atmosphere by 2045. Currently, more than 60 percent of the nation’s electricity is generated from burning fossil fuels like coal, natural gas and petroleum.

Much of the resulting media coverage has focused on electric alternatives, which has some experts questioning where that surge in power will come from—whether nuclear, hydro, wind or fossil fuels.

Blume has different ideas.

“I think the car companies will take advantage and carve out a profitable niche for high-mileage clean-alcohol-only cars,” he says. “They will produce less climate change gasses and pollution when compared to [what generates] our current electricity.”

SCALING UP

Blume’s decades-long education efforts hint at what Whiskey Hill Farms cultivates as much as anything: knowledge. That takes many forms.

Whiskey Hill Farms holds regular farmer workshops, some underwritten by a grant from U.C. Davis’ Sustainable Ag Program. NASA staff have swung by for a learning day and organic lunch. Rep. Jimmy Panetta (D—Carmel Valley) took home turmeric root as part of his tutorial. Open Farm Tours and visits from EcoFarm Conference attendees—and forthcoming farm stand sales on property in 2023—will further enlighten Central Coast residents and visitors.

Meanwhile, WHF and Blume Industries have received multiple grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s sustainable division to teach underserved area growers closed-loop and regenerative ag. That helped inspire the USDA to recently dedicate funds to developing a regenerative curriculum—in Spanish—that can be exported around the country.

As this goes to print, a Calabasas Elementary School Victory Garden program is starting to sprout things at Whiskey Hill like radishes, bok choy, tomatillos and turnips.

Blume is willing to walk anyone interested through his closed-loop techniques. He’s happy to detail ways to adapt gas-powered vehicles to run on alcohol, or how electric and solar energy present costs and challenges alcohol doesn’t, though he advocates hybrid designs using ethanol and electricity.

Santa Cruz City Manager Matt Huffaker received a starter course in how alcohol can help a municipality while at the same post in Watsonville. He collaborated with WHF and school district officials on a pilot to run two school buses on farm-grown fuel, a project currently on hold while awaiting additional support.

“Whiskey Hills’ process reminds me of the scenes from Back to the Future, when Doc Brown was stuffing banana peels and garbage into his DeLorean for fuel,” Huffaker says. “The future is now, and we’re fortunate to have this disruptive technology in Santa Cruz.”

Obeying his default setting, Blume is aiming to go bigger than local government. On his website, he has published a “14-Point Plan for U.S. Energy Independence.” He has given it to several Congressional representatives while encouraging citizens to share it with their reps and friends. Among its key provisions are taxing oil companies fairly to create a Fueling Democracy Fund that supports local production of alcohol, increased alcohol use and the stockpiling of alcohol reserves to prevent energy crises; reducing crop certification time so surplus and/or high-energy plants like recently approved sugar beets don’t take forever to become a fuel source; and providing food-waste-to-fuel production credits.

Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D—San Jose) ranks as the second most senior member of the House Science, Space and Technology Committee, and is among those who have received the plan and visited Whiskey Hill. While acknowledging obstacles, she sounds optimistic Whiskey Hill lessons can serve as a starting point.

“Any time you make a change, somebody is upset—people who are wedded to the status quo don’t want the status quo to change—so how do you overcome the institutional barriers to get something done?” she asks. “You have to prepare to act when opportunities exist. Some of this may be holding hearings, so the concept is not unknown, [and] introducing bills for pilot projects. Nothing changes without people pushing for change.”

She admits the solutions to complex problems don’t frequently come from within the government or in a sweeping fashion, and that replicable models are vital while the public is primed to receive them.

“If you can prove a concept, you can scale,” she says. “Sometimes, you have to have incremental progress before you make everything happen. Given the state of climate emergency, voters are aware we have a very serious problem: Our children and grandchildren are going to face climate extremes we’ve never had.”

When asked if the plan can seem overly optimistic—particularly given the power Big Oil deploys with what Blume calls “bare-knuckle capitalist fighting”—she pushes back.

“If you don’t have aspirations, then you never get anywhere,” she says. “Maybe we couldn’t do all 14 points, but [we] can do proof-of-concept stuff. It’s important.”

When Blume hears these thoughts—and fields questions as to whether he feels dismayed that little has changed since the late 70s energy crisis—he provides pushback of his own.

He notes alcohol fuel production was a big fat zero back then, compared to over 15 billion gallons of alcohol produced annually. He reminds anyone who will listen that 50 countries worldwide are engaged in converting to ethanol on some level—and Brazil has converted completely.

“It’s not fair to say we haven’t made progress,” Blume says. “It’s normal for struggle to occur early in the implementation of a new idea. Then, all of a sudden, everyone knows you have the right answer, and it happens overnight. And it seems like magic.”

PERMACULTURE PARADISE

Palatial palapa suites. Curving white sand beaches. Sweeping views of flamingos flying over turquoise seas.

Necker Island looks like what you’d imagine Sir Richard Branson might develop with a private 74-acre paradise.

Addis Ababa, on the other hand, represents a different reality. Ethiopia’s sprawling capital brings on urban intensity, inspiring architecture and vibrant culture, with a heavy overlay of smoke from locals burning wood—indoors—to cook or stay warm, on the outskirts, at its center, everywhere and often all at once.

That sets off cascading problems that feel like the opposite of Blume’s looping benefits. Disease-causing smoke and carbon monoxide inhalation are common. Complications result before and after birth. Wood demand drives deforestation. In fact, as half of the world cooks and heats with wood, the burn has become the third largest source of carbon dioxide emissions on Earth while taking out the trees that would absorb them.

But it turns out that Branson’s remote hideaway in the British Virgin Islands and population-3.7 million Addis Ababa have more in common than most would think.

In both places, alcohol provides a novel solution.

Blume visited BVI recently as part of a group presenting eco-investors with ways to fund technology-driven innovation that benefits the environment. Branson directed his staff to learn more about Blume’s systems, and now they’re in preliminary talks to try converting the island’s watercraft to ethanol engines. Meanwhile, Blume hopes a Necker’s Nectar flavored vodka, made with passionfruit from the island, might sell at its on-site bars.

“We could sell it all over the island,’” he remembers Branson saying.

Blume’s tech has implications for less luxurious islands everywhere—they typically depend on big diesel generators that spew greenhouse gasses at costly rates. Less shipping, soot and stink is within reach.

In Ethiopia, meanwhile, the presence of a Blume-designed micro-distillery has a macro impact.

Working in concert with Project Gaia—whose mission is to prevent energy poverty with safe and efficient alcohol fuels—a local women’s association feeds the distillery molasses from local sugar cane and makes clean-burning ethanol and a potent fertilizer. The fuel then goes into special Cleancook stoves that burn the equivalent of 17 pounds of wood with 1 liter of ethanol, without the lung poison.

“This is the way of the future: All of the resources available can be used and reused,” says Gaia Executive Director Harry Stokes, who has worked with Blume for 15 years. “Africans key into this immediately. It’s not ‘bigger is better’ like in the U.S. If they had better access to capital, David’s plants would be all over the continent.”

Together, Necker Island and Addis Ababa indicate how widely alcohol can apply across geographic and socio-economic boundaries.

A lot falls between those extremes. Farms here and abroad can turn bigger profits by raising energy crops over traditional crops, earning tax credits and creating their own fuel and high-grade fertilizer. Consumers can use alcohol blends in existing vehicles and limit payout and emissions. Preppers can grow their own fuel. Permaculture fans can create their own closed-loop systems. Cities can transform food waste—now mandated by California law to be kept out of the landfill, ramping up need—into alcohol to run municipal vehicles.

“People assume when we talk about gas replacements, we mean cars,” Blume says. “It goes far beyond that.”

He believes alcohol can affect not just farm, transportation and energy policy but international policy. (Blume and company prefer “alcohol” over “ethanol” because the latter comes with preconceived views after decades of oil industry messaging, though they’re the same thing.) He imagines a scenario where the U.S. and European countries stockpile easy-to-make and renewable alcohol, so they feel less dependent on, say, Russia.

To that end: The war in Ukraine triggered more than a reckoning on oil dependency, including a fertilizer shortage—and a corresponding spike in prices. Alcohol’s got you there too, Blume adds, pointing to the super juice fertilizer he makes with outflow from his alcohol still.

“The bottom line: If God ever wanted to create a clean fuel for humans, it would’ve been ethanol,” Stokes says. “We better get busy and use it.”

FUEL FACTOR

Last fall, Blume set sail for the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference (aka COP26) in Glasgow, Scotland.

He was invited to COP26 by an eco-tech nonprofit, Innovation 4.4, partner to the organizing United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, as part of a pavilion featuring advanced regenerative technologies.

He and long-time collaborator Chris Patton described how evolving their combined systems—including a solar-powered thermal reactor that can transform plastic and even nitrogen in the air around us into fuel—is not far off.

Like many of Blume’s undertakings, plastic-to-alcohol sounds outlandish. It is, and it’s also true—which Blume says had government ministers swarming their pavilion for more info on what they can do.

“We had so many people coming to our booth saying, ‘Everyone else is talking about measuring and legislating our problems; you’re the only guys in the conference who have solutions,” he says. “As a farmer, I don’t talk; I get out there and build it. The world needs to stop talking and do it.”

More information on David Blume’s work is available at whiskeyhillfarms.com, alcoholcanbeagas.com and projectgaia.com.